- ...

Postgraduate Studentships - Search for funding opportunities.

Postgraduate Studentships - Search for funding opportunities.

When I was looking at where to do my PhD, one of the real draws of Plymouth was its proximity to the Cornwall and Devon coast.

Having grown up in the countryside, I have always been drawn to natural open spaces especially when it’s adjoined by coastline. This is at its most spectacular in Devon and Cornwall which, in my opinion, is the prettiest area of England. Having these areas so close to Plymouth made the opportunity to live and study there a big attraction.

By the time I started my PhD, the Lyme Bay Marine Protected Area had been in effect for around 10 years. Dr Emma Sheehan and her team had monitored it yearly for that whole duration and the accompanying dataset was, and probably still is, of a uniquely high resolution. To have a decade of data compiled using consistent survey techniques and methods is almost unheard of.

Added to that, there is the combination of both towed underwater video (to survey all sessile and sedentary species) alongside baited remote underwater video systems (to survey all mobile species attracted to the bait). That results in the assessment of a wide range of species, from sessile/sedentary pink sea fans all the way up to sharks and rays.

I immediately began looking at how to use it to assess the protection that had been applied within Lyme Bay, and publicise any found benefits or disadvantages of the management style that had been applied.

That data analysis has dominated my winter months for the past four years, and I have spent countless hours on data handling, data manipulation, data archiving and data analysis. This needed to be done in a repeatable way as every year we would collect new additions to the data, across very large datasets.

We also wanted to create technical documents of publishable quality and in a way that could be reproduced by others who may want to replicate our work. All these requirements led to extensive use of the programming language R.

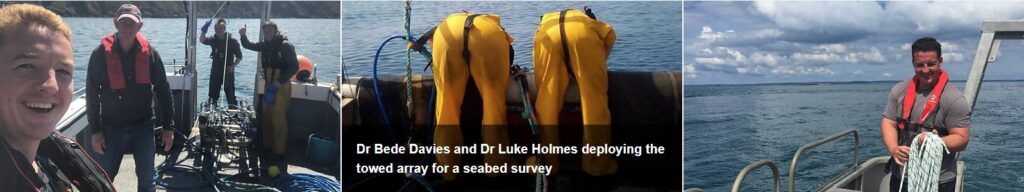

For the other half of the year, my time was dedicated almost exclusively to fieldwork and this was a far more physical and practical role. Fieldwork, especially when in the marine environment, requires a fair amount of early mornings, kit servicing and planning.

Due to us relying heavily on underwater videography a standard day would consist of early wake up, onto the boat and a day of videoing the seabed with its surrounding flora and fauna.

Our evenings would then be filled with backing up videos and recharging batteries before giving ourselves time to recharge and prepare for the next day of work.

While carrying out fieldwork in Lyme Bay we used local fishers’ boats to deploy equipment, and this has meant spending many hours at sea with a range of different fishers. Their wealth of knowledge, and seemingly unending stories from in and around Lyme Bay, is astonishing and has been very interesting.

The MPA in Lyme Bay, and the involvement of fishers in helping to assess it, is now being used as an example of a success story in the planning of marine management across the UK and further afield globally.

The main finding of our studies was that, when protected at a whole ecosystem rather than a habitat level, marine areas can show recovery in a matter of years.

This can be across many parts of the ecosystem, not only the sensitive species but also those that continue to be fished higher up the tropic chain/food web. It showed that this type of protection is not only benefiting conservation targets but also aiding nearby fisheries. What was surprising was the rate that change happened.

Many papers looking at MPA recovery following the closures of fisheries predict it would be around ten to 15 years before noticeable change would happen.

However, the results from my PhD show that Lyme Bay experienced rapid change within a couple of years and has continued to change over the whole time series.

My PhD spanned the COVID-19 pandemic which, as for everyone, posed a number of significant challenges. For a while, that did limit the time we were available to spend in the field but I managed to find ways to endure through that in whatever way possible. Other than that the main challenges were learning the new skills and techniques required for completing a PhD. Thankfully, I thoroughly enjoyed that and would happily do it again.

Throughout all of my research, academics from the University have been very supportive. It has been brilliant to work with a great network of researchers from different fields, all of them keen to meet and discuss their work, and offer advice and guidance where they could.

I think my main hope would be that MPAs are implemented using the best available research. In saying that, I don’t mean only perhaps my work but specific research to the individual areas. The marine environment is naturally highly changeable on many different spatial scales so when combined with changeable human pressures local research will be very important for marine management.

My research has shown that when allowed to recover on an ecosystem level MPAs can hit targets for both conservation and fisheries. This should be a key target for all MPAs now and in the future.

Find out about postgraduate study at the University of Plymouth here

Postgraduate study opportunities at University of Plymouth About us At the University of Plymouth, we are proud to be one of only a select number of ...

Sign up to Postgraduate Studentships

Sign up to compare masters

Thanks for making your selection. Click below to view your comparisons.